Vinod Khosla on How to Build the Future

by Y Combinator1/9/2019

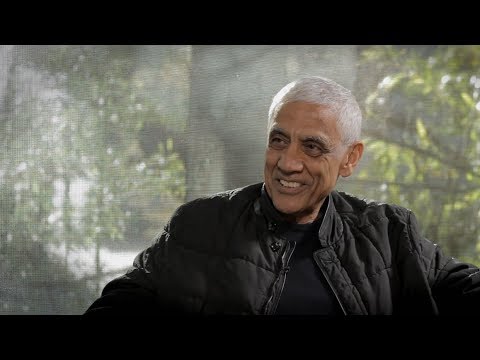

Vinod Khosla is the founder of Khosla Ventures, a firm focused on assisting entrepreneurs to build impactful new energy and technology companies. Previously he was the founding CEO of Sun Microsystems, where he pioneered open systems and commercial RISC processors.

How to Build the Future is hosted by Sam Altman.

Topics

00:00 – Vinod’s intro

00:40 – A zero-million-dollar company vs a zero-billion-dollar company

3:50 – What percentage of investors in Silicon Valley are good long-term company builders?

4:20 – Who has earned the right to advise an entrepreneur?

6:20 – Which risk to take when

6:50 – Helpful board members

7:45 – Who to trust for what advice

10:30 – First principles thinking and rate of change

12:30 – Evaluating a candidate in an interview

13:45 – How much should a founder have planned and how ambitious should a founder be?

16:00 – Recruiting great people

18:30 – Building a phenomenal early team

19:50 – Being generous with early employee equity

26:48 – The art, science, and labor of recruiting

27:50 – How founders should think about investors

30:30 – Doers vs pontificators

31:30 – What does Vinod want to do in the next ten years?

31:40 – Reinventing Societal Infrastructure with Technology

Subscribe

iTunes

Breaker

Google Play

Spotify

Stitcher

SoundCloud

RSS

Transcript

Craig Cannon [00:00] – Hey, how’s it going? This is Craig Cannon, and you’re listening to Y Combinator’s podcast. Today’s episode is with Vinod Khosla and Sam Altman. Vinod is the founder of Khosla Ventures, a firm focused on assisting entrepreneurs to build impactful new energy and technology companies. Previously, he was the founding CEO of Sun Microsystems where he pioneered open systems and commercial risk processors. You can find Vinod on Twitter @vkhosla and Sam is on Twitter @sama. Alright, here we go.

Sam Altman [00:30] – My name is Sam. Today we’re talking to Vinod Khosla. Vinod is the founder of Sun Microsystems and Khosla Ventures. He’s been involved in the creation of dozens of billion dollar companies, and I think he’s one of the most interesting thinkers that I’ve ever spoken to about how to build an ambitious company, and team, and everything else you need, so thank you for taking the time to talk to us today.

Vinod Khosla [00:51] – Great to talk about it.

Sam Altman [00:53] – I want to start with the very beginning, and how to think about the idea and the mindset for a company. One thing you’ve said before I really love is that there’s a huge difference between a $0 million company and a $0 billion company. And maybe you could start with just explaining what you mean by that.

Vinod Khosla [01:10] – To me, when you set out on a journey, your mindset determines who you bring onboard, how you approach it, what you set up, what deals you do, which investors you’ve got. In a zero revenue company, if you take zero million, you’re thinking a certain way to tactically achieve a small, short-term goal. $0 billion dollars, you start building from day one the company and the people you’ll need to build the company. One of the things people seldom realize when they’re starting up, you don’t ever plan what you’re going to do. You build a plan to make to plan. Who helps in that planning as you plan iteratively, as you evolve your strategy and your tactics, that team, which I call the kitchen cabinet of a company, is the essence of what your company will become. One of my favorite tweets I like tweeting out is, “A company becomes the people it hires, not the plan it makes.” That’s grossly underappreciated.

Sam Altman [02:24] – Is the biggest difference between the zero million and the $0 billion company the initial people you hire, in your experience?

Vinod Khosla [02:30] – It is the initial people you hire, but also, how you approach the initial tactics. My other great analogy, if you have a large vision, you’re climbing Mt. Everest. It’s never a straight line. Nobody’s climbed Everest in a straight line. You get to base camp, you get to camp one, camp two, camp three, camp four. If you get the right approach, you’re obstinate about your vision, which is Mt. Everest, but you’re flexible about tactics as things change, as you zig and zag, when you pivot, these are all things on the way to staying with the vision. Now, you can also do the same tactics without worrying about the vision, and my big beef with a lot of investors is they want revenue, they want to meet plan, as opposed to collect assets for this larger assent to Mt. Everest. You can clearly set up base camp where you get revenue, stability, cashflow, breakeven, the ability to raise more money in the wrong place. If your goal is to get to Everest, but you still get the revenue, you might have 20 million, 30 million, 100 million of revenue, but it doesn’t help you get to Everest. Or you could take a little longer, a little harder, get to the base camp that lets you get the resources to keep the journey to your vision. there’s a huge difference, and the key is the biggest difference, but there’s also strategy differences.

Vinod Khosla [04:10] – By the way, investors, in my view, matter a lot in this because you make short-term versus long-term trade offs.

Sam Altman [04:17] – What percent of investors in Silicon Valley do you think are good long-term company builders?

Vinod Khosla [04:25] – I get in a lot of trouble for saying this–

Sam Altman [04:27] – We’re among friends. It’s okay.

Vinod Khosla [04:29] – 90% of investors add no value. My assessment, 70% of investors add negative value to a company. That means they’re advising a company, this is part of team building, too, for entrepreneurs. They’re advising a company when they haven’t earned the right to advise an entrepreneur. Some of the junior people here when they ask me, “Hey, at this other firm young people going on boards cannot be on the board.” I say, you haven’t earned the right to advise an entrepreneur, so it’s unfair to the… Just because you got an MBA and joined a venture firm doesn’t mean you’re qualified to advise an entrepreneur. The biggest piece of it, not the only way, is have you built a large company? Have you gone through how hard it is, how uncertain it is, how traumatic it is to go through? Just this morning I was talking to somebody about how many times we almost worried about making payroll at Sun, of going bankrupt. Plenty of times!

Sam Altman [05:34] – Like more than two?

Vinod Khosla [05:35] – There was a three month period where we almost went bankrupt because we had a hardware problem. Monitors we were buying from Philips were breaking every 30 days. There was probably a month or two when the earliest I went home was at 3 AM, and the latest I was back in the office was 7 AM. Unless you’ve you’ve felt that gut-wrenching decision, you can’t advise an entrepreneur. I hate board members who sit in a board meeting and say, “Oh, can you improve quality?” And then five minutes later, “Can you ship faster?” And five minutes later, “Spend less money?” And they’ve never gone through really hard trade offs and how uncertain it is. If you add more people and increase your burn rate, are you going to improve and hurt your chances of getting something out? These are very uncertain, very hard calls. The biggest thing an entrepreneur deals with is which risk to take when. When you take a financial risk of running lean, when you take an engineered marketing risk of a feature-poor product, when you take which risk do you want to take, and it’s like whack-a-mole. Ambiguity is so hard to deal with, but it’s the essence, and frankly, it’s one of the areas where entrepreneurs, when they don’t think about what they actually need, pick the wrong people. If somebody’s never dealt with this decision making under ambiguity, and they’re in a big company, they’re not qualified to help you.

Sam Altman [07:22] – One of the things I hate about board members is when you’re doing that, making these, deciding which risk you want in the stressful environment, the thing you most want as an entrepreneur is a board that you feel is calming you down, is supporting you, is not adding the stress. Most board members, while you’re doing that, just tell you, “Oh, you’re going to die.” The thing I hate the most is when an old board member of mine used to send me press clippings of competitors all the time to make a point. You really just want someone who’s like, you got to take a hard risk here. It’s a tough decision.

Vinod Khosla [07:54] – Look, these things are the things you’re not qualified to advise an entrepreneur on if you haven’t been through one. There is a time when panic is the appropriate response in a company. It does happen.

Sam Altman [08:10] – One thing that I’ve noticed entrepreneurs that are working on hard, ambitious companies really struggle with is figuring out who to trust for what advice. How do you think about that?

Vinod Khosla [08:21] – My big advice, and the first piece of advice I gave Joe Kraus when he was starting Excite was the single hardest decision you’ll make is whose advice to trust on what topic.

Sam Altman [08:34] – Is that the answer?

Vinod Khosla [08:35] – Now, if you’re 20 years old, do you ask your dad, or your friends? If you have a marketing problem, do you ask somebody who’s done marketing at IBM? They’ve never dealt with things where the market isn’t established. It’s incremental year to year, 5% improvement is what they’re shooting for. They’re not qualified to invent whole new markets, whole new approaches to markets. Those are really hard decisions, and that’s where nuanced advice of which employee would be better. The funny story that’s actually not known very much is Scott McNealy, when we started Sun, he started as a VP of Manufacturing.

Sam Altman [09:22] – I did not know that.

Vinod Khosla [09:24] – Almost nobody knows that. At one point, I said, “Scott, you’ve got to become our VP of Sales.” Because of certain types of behaviors. But his background was in manufacturing. You have to make those gut calls. It’s a very non-intuitive gut call, so you have to make those. But back to this issue, whose advice to trust on what topic is the single hardest decision an entrepreneur makes. It’s also where the right investors can really help you. I had an argument just last week with another co-investor. In a healthcare company, they wanted this healthcare person who had never dealt with change beyond 2% a year. Experience doesn’t matter, the rate of learning matters. First principle’s thinking matters. Pick for the best athlete, not the person who’s the most established wide receiver who knows how to run one pattern, and one pattern only.

Sam Altman [10:24] – There’s two things I want to follow up on. We’ll get to the athlete in a second.

Vinod Khosla [10:28] – We’ll keep running into things we want to follow.

Sam Altman [10:30] – Ee will. I agree, it’s really hard to know whose advise to trust, but a 20 year old entrepreneur comes in here, no work experience, you decide to back them. You have to give him or her advice and say, “Here’s how to do this.” What do you say? How do you know whose advice to trust, tactically?

Vinod Khosla [10:49] – I look at not what entrepreneur is saying. We always have this debate inside of them, too, but how they’re thinking about the problem. In first principle’s thinking, if you give them brand-new problem. I’ll often say, “Hey, if you were doing this other startup, how would you approach it?” If they have to think from scratch on a brand-new problem, and by the way, this is a great interview question, that they’ve never dealt with, they don’t have any experience with, how do they approach it? Is probably the best indicator of how fast they will learn. If I have pick between lots of–

Sam Altman [11:26] – Including learning how to trust different people’s judgments?

Vinod Khosla [11:29] – Including learning who to trust and which people to trust. This becomes sort of this nuanced thing. I’m sure you’ve noticed one of the things we look at YC stuff, in the three months that they’ve been at YC, what’s their rate of change? If we’ve had multiple points of intercept. That may be a stronger indicator than any other single–

Sam Altman [11:55] – That is my number one.

Vinod Khosla [11:57] – Right?

Sam Altman [11:57] – That is my number one, by far.

Vinod Khosla [11:58] – Right. We always say, how fast did they evolve their plan, change their plan? What it’s first saying to me with other investors, they say, “Well, stick to your plan,” or, “Are you executing on your plan?” I’m the exact opposite. How fast are you evolving your plan, or changing your plan, and learning? But building that team, so this brings up a related issue we should talk to since I’m more focused on people. When you hire a VP of Marketing, and I’ve said this to you before, one question, the functional question is, can you do marketing? But that’s not the most important question. If he’s one of top five people in the company, the most important question is, what are the questions he will ask? How will he make the CFO better or the VP of engineering better through the questions they ask? Which then prompt this kind of thinking, which then leads to a better kitchen cabinet. The people you coalesce around your dining table when you have a really hard, ambiguous, uncertain decision to make.

Sam Altman [13:07] – How do you evaluate that in an interview? You’re interviewing a VP of Marketing. You want to know if they’re going to make the CFO better. How do you probe that?

Vinod Khosla [13:14] – People often say, here’s what happened at my company. I’ll say, “If you were CEO, and you had to make a different set of decisions, what would you do?” Have them think under circumstances. Or if you’re doing this other startup, one of my favorite questions in startup world is, if I gave you $10 million today, what three startups would you consider, and what are the reasons as an investor you wouldn’t want to invest in those? You suddenly get how they think about a new problem, which is what you face every day in a startup.

Sam Altman [13:53] – It really is true that the, I think one thing everyone underestimates when they start a startup is just how little of the problem they’ve already thought about, and how much more is going to reveal itself every week.

Vinod Khosla [14:04] – I often tell enrepreneurs a business plan is completely irrelevant, other than to judge how somebody’s thought about a problem. Not what they’re going to do.

Sam Altman [14:15] – Speaking of that, how much do you expect a founder to have figured out early on, and how ambitious should a founder be? How ambitious were you when you started Sun? How much of Sun had you figured out? How much of that vision stayed true to what happened?

Vinod Khosla [14:29] – I’d say I was very ambitious. I’d done one other startup before that was also pretty successful. Daisy Systems. That went on to go public in the ’80s. Raised $100 million, which was a huge IP in those days. I was very ambitious, but because I was much more passionate, and passion’s an important ingredient we should talk about, especially in IT, I was passionate about what I wanted to get done, not about the IRR, or the returns. I like founders who are very ambitious, mostly because if they’re not ambitious, they’ll hire a team to build a $0 million company. If they’re ambitious, they’ll hire a team to build a $0 billion company. Among the first 15 people at Sun, 15, 20 people, we hired Eric Schmidt, who went on to run Google. I didn’t know he was going to be that capable. We hired Carol Bartz who ran Autodesk, and then Yahoo. Hired Bill Joy, who wasn’t part of the initial founding team. We recruited him as a founder after the fact. We hired so many other people. Guys like Tom Lyon and Bob Lyon, each of which have started billion dollar companies. Larry Garlick who nobody knows now, who started Remedy. Andy Bechtolsheim himself has started so many companies. There was such an incredible talent pool there.

Sam Altman [16:22] – This I really want to dig in on. There’s only a small handful–

Vinod Khosla [16:25] – By the way, I just want to take one small diversion. When I met Andy, he was in Margaret Jacks Hall at Stanford. He said, “Why don’t you license the technology for $10,000?” He had licensed it to six other startups at 10,000, which in the ’80s for a graduate student was a shit-load of money. In fact, one of those companies Simplink, was funded by Kleiner Perkins and John Doerr was on the board. They took the license. I said, “Andy, I want the goose that laid the golden egg. I don’t really care about the golden egg because it will be irrelevant in a couple years.” I didn’t know why, but part of it was I just loved interesting people. I gave him half the equity just to join, and then I did a sales job, and selling is an incredible part of being an entrepreneur, into dropping his PhD. Best decision I ever made. Best decision he ever made, but it was a hard sales job to convince him. I sort of say in recruiting, a no is a maybe, and a maybe is a yes, and that’s sort of my job. I get very disappointed when I can’t get a yes–

Sam Altman [17:49] – How long did it take you to get him from a no, to a maybe, to a yes?

Vinod Khosla [17:52] – A couple of months, but Bill Joy took six months because I also had to convince him to drop his PhD. Two people dropped their PhDs.

Sam Altman [18:01] – The very best people I’ve ever recruited in different places in my career have all taken at least months to recruit. Because they always have something great to walk away from.

Vinod Khosla [18:10] – The people who don’t have something great to walk away are probably the people you don’t want.

Sam Altman [18:16] – Absolutely, yes.

Vinod Khosla [18:17] – Especially when you’re thinking beyond dysfunctional, and the people who do job X well. Whether it’s marketing, or database architecture, or whatever, are thinking linearly. If they are broad thinkers, which is what’s key to that kitchen cabinet that helps you evolve a plan, you need people who are so full of ideas, they’re always triaging down to the thing they can do.

Sam Altman [18:43] – People like that always have great opportunities so it’s hard to get them to join as an employee because they can start their own–

Vinod Khosla [18:47] – And you chase them forever.

Sam Altman [18:49] – This is actually what I wanted to go to next. There’s a handful of companies that have been able to get those people in the early 10, 20, 30 employees that could go start their own company, and that go on to later. PayPal’s a famous example, Sun’s another one. What did you do at Sun, and what has happened at other companies where you’ve seen this? Where people build this phenomenal early team that goes on to be wildly successful.

Vinod Khosla [19:12] – Entrepreneurship is a funny thing because the vision is impractical. If you’re reasonable, you won’t do unreasonable things. It’s just by definition. If you have great managers, good process people, they will work against, align the company to become great. They’ll take a great idea and turn it into a good one, and execute a decent idea at lower risk that’s more reasonable, more sensible. That’s an okay goal to have if that’s your goal. If your goal is something unreasonable, something ambitious, really visionary, something change the world, then you have to take the other approach. Get this. Think tank of unreasonable people together, and below that, layer the reasonable people who will micro-optimize within the macro ideas that the kitchen cabinet comes up with.

Sam Altman [20:18] – How do you think about the equity that it takes to attract these kinds of people?

Vinod Khosla [20:24] – I see this as a major problem nowadays. People aren’t allocating equity widely enough. Among the first three or four founders at Sun, we kept less than half of the common, which was just the total was something like 25 to 27% for the founders, and equal or slightly larger chunk for everybody else we would hire, and then investors had minority, but a significant minority. It was like 40% for investors after the A round. Something like that. In retrospect, that was a very good idea. When last year my son started his company, I said, keep 15% for yourself instead of 45. He could’ve done either number. Try and hire one or two people at 15%, even though they’re coming later, even though they didn’t come up with the idea, but that would be incredible resources. Especially magnets to attract other people, or bring essential skills.

Sam Altman [21:36] – Can you say what you mean by a magnet to attract other people?

Vinod Khosla [21:39] – If you believe a company becomes the people it hires, then your key task becomes attracting the people. There’s also using them productively. That’s a management skill. But attracting people becomes who finds you attractive, and selling depends on magnets. Bill Joy was an incredible magnet even back then. Even though Open Source didn’t exist the way it does today, people wanted to work with Bill and Andy. Even if Bill didn’t do a day of work, he was more than worth it because he helped attract Eric Schmidt. I don’t think Eric would have come work for me as a 25 year old, other than I did have a convincing power of why this was going to be large. We discarded, for example, the notion that, which most investors said, “Why don’t you be a graphics add on terminal to DEC VAXes?” There was established known market. There was no graphics terminal. There was a company in Utah, Evans and Sutherland that built graphics terminals. It was easy. You wouldn’t do distributed computing and nobody had heard the term. When we released NFS, there was no distributed file system in the world, and we open sourced it, and people first said, one, “Who needs distributed computing?” The second question was, “If it’s important, why are you giving away all your intellectual property?” The specifics don’t matter. Thinking non-linearly about it is what matters, and that’s what the team enabled. Full circle back to equity, as much as dealing 30% of the pool to non-founders. Neal took 15%. He recruited in his other startup Curai.

Vinod Khosla [23:48] – He kept 15%, hired 15%, a co-founder for 15%, and then left the rest to hire great employees. Now, it is dependent on the area you’re working in. He was working in AI. He wanted the people who were all making million dollar salaries at Google, and Uber, and other places, as engineers. You had to give them three, four, 5% each, and you’d normally not think about it, but if you’re competing in an AI startup, you’re not going to get the best talent, and especially if this issue we talked about earlier, if somebody can do their own startup, they will. They’re not comparing them to your job. You’re comparing them to them starting their own company. And so, and if you don’t do that, you’re including only the people who couldn’t start their own company who won’t help you evolve your plan.

Sam Altman [24:46] – A thing that I hear a lot is I can hire an engineer for X per basis points, so why would I ever pay 5X or 10X? Then I always say, “Wait, in two years ask me again if that was the right decision.” But the quality of people you can get if you’re super generous with the equity. I think this is the shape of things to come.

Vinod Khosla [25:05] – This is my single biggest beef with YC. Not enough option pools. Not enough option pools, not enough focus on recruiting the right co-founders. I was fortunate, Neal trusted me so I could shepherd him into sort of a very different approach. He may have had the highest option pool in his batch.

Sam Altman [25:30] – I have found that it’s harder to convince founders of this than I would’ve expected.

Vinod Khosla [25:36] – Because it’s not intuitive.

Sam Altman [25:38] – Well, also most investors say make the option pool as small as you can. Because neither investors nor founders want to, they’d like to own as much as possible, and it sounds really good. Until you’ve felt it, it’s hard to convince them.

Vinod Khosla [25:49] – They would like to own a higher percentage, but the pie is much smaller. If you sort of say I’m maximizing the size of the pie first, then it doesn’t matter what percentage you own.

Sam Altman [26:04] – This is the most important piece of advice that we’ve talked about, among many important things today. Being super generous with early employee equity in getting founder quality people is the first 10 employees. All the evidence is on the side of doing this, and yet almost no one does, so there’s a huge edge if you’re willing to do it.

Vinod Khosla [26:22] – Absolutely. 100% agree that this ends up being the single most important thing in the first six months of a company, and it’s incredibly important. In fact, I’ve written two pieces on it. One, once you’re doing a startup, how do you engineer the gene pool of a company? And there’s an important part. You sort of have to have a process. I find it silly to advise people to hire the best team, because everybody says that. It’s not actionable. When you follow this process I call gene pool engineering, you are trying to maximize your chances of success, and you’re minimizing the risks you’re taking on by virtue of the team you’re building. That’s one part of it, and that’s sort of more mechanical. The other part is your functional hiring. Hire VP of Engineering, hire a VP of Marketing, hire a CFO, hire a VP of Customer Support. You do hiring for this non-linear stuff. How does your VP of Marketing improve the quality of your VP of Engineering? Make them think harder? This sort of non-linear thinking is, and I’ve written a different piece called, I think The Labor of Love: The Art of Hiring. Something like that on our website. That’s a long piece about this. Both these were a couple of years in TechCrunch. They’re essential reading for entrepreneurs, in my view, even if they don’t follow the advice, it’ll change how they think about the problem.

Sam Altman [28:02] – We will add the links to our website. One final question, one area to wrap up on. We’ve talked a lot about how to pick your employees, your team members. It’s almost as important to pick your investor, as well. How do you advise founders if they’re trying to build a significant company that’s going to do something very disruptive, be around for decades, how should they think about their investors?

Vinod Khosla [28:25] – Every piece of equity you do, the money you get is the smaller part of what you get. Advice and the right approach is the much more important part. It’s a simple thing. There’s investors who are happy with three times their money, in fact, want to sell as soon as they can and make 3X, 4X, and people who care about your vision. Or people who understand the technological approach you’re taking and will be much more tolerant as things go wrong. Those are the factors I suggest people optimize for.

Sam Altman [29:02] – How do you tell? How do you know if an investor truly cares about your vision?

Vinod Khosla [29:06] – Talk to other founders, especially founders who’ve gone through a large promise, large vision, and had hiccups along the way. When things go wrong along an ambitious path is when you can actually judge an investor. How they think about hiring. Look back in retrospect couple of years later or talk to founders who can and say what worked and what didn’t? Those are the key questions. An investor is an employee who you can’t fire and that’s how you should think about it, otherwise all the same principles apply. I get very frustrated with investors because they mostly detract from value. Most investors are negative value add to a company that’s trying to be ambitious. If they’re just trying to get to liquidity as soon as possible, then there’s plenty of investors who do that well.

Sam Altman [30:03] – Have you had founders who come pitch you and you say that’s too ambitious?

Vinod Khosla [30:08] – I’ve never had that happen. I have had the following conversation. That’s ambitious. That’s awesome. Build the team for it. Now, what is step one, two and three? Let’s be thoughtful about how you discover the risks on the path to the vision. Beause frankly, achieving a large vision is first about discovering what’s hard, what the problems are, what else influences success along that path. Once you’ve found the problem, and which you can only discover by doing things, then you can…

Sam Altman [30:46] – The only recipe I’ve ever seen work for making really impactful companies is both the giant vision and a good step one, two, and three. You have to have both, and neither without the other will work.

Vinod Khosla [30:59] – By the related thing, I often tweet this, I hate pontificators. So easy to do studies, so easy to opine on things. I love doers versus pontificators.

Sam Altman [31:10] – Me too.

Vinod Khosla [31:11] – And Nassim Taleb has written Skin in the Game, but also, not so much Black Swan, but his second book after that. Skin in the Game is about doers versus pontificators. Then he has another book about the right kinds of asymmetric risks to take that he wrote after The Black Swan that I feel is more important than Black Swan.

Sam Altman [31:41] – One thing that has just worked for me again and again in my career is I happen to love doers and I don’t love talkers, and I just got lucky because I bias the people I surround myself with so far in that direction. It’s been great. Final question, what do you hope to get done in the next 10 years? What are you most excited about doing now?

Vinod Khosla [31:58] – I’m 63. I actually at 60 defined what I want to work on for 20 years. I wrote a piece called Reinventing Societal Infrastructure with Technology. It’s about a 50-page document. It was the following exercise. I won’t go into the details because we don’t have enough time. I said, if I took the US GDP, what parts of the non-governmental GDP could I reinvent personally with technology? I expected I’d come up with a small part of the GDP that was open to working on. Turns out, there’s no part of non-governmental US GDP that one can’t innovate on in ways that are not five, 10% improvements, but are 100 to 1,000% improvements in resource and works. I sort of decided if seven billion people on the planet want the lifestyle that 700 million people, the top 10% have, and that 10% has an energy-rich lifestyle, a healthcare rich style, a education-rich lifestyle, a transportation-rich, you get the idea, the very rich lifestyles, without destroying the planet, could we get seven billion people the lifestyle of the 700 million people? Then without destroying the planet and without needing 10X of everything, could you do it? I could think of a way to do it in every major part personally. Only thing I’m short is entrepreneurs. I subtitled this document, “A Call to Entrepreneurs.” It’s amazing because no part of the GDP’s immune to innovation. Five, six years ago when Pat Brown said he wanted to eliminate animal husbandry, they came very clear we could change how most of this planet’s usable land area is used. Most of the land on this planet.

Vinod Khosla [34:12] – And that’s Pat’s mission, and I think I said yes to him in our very first meeting we’d invest. I didn’t even need to know the details. It was just a vision too big to not attempt. Hamburgers to rocket labs doing rockets which we did about the same time, to my new passion. Could you build buildings with 80% less material? That’s why I’m so excited about 3D printed buildings. There’s nothing from food, to building, to construction, to rockets, to everything computation enables. From AI, to it’s really exciting, and I feel like 20 years is not going to be enough. I hope I stay healthy.

Sam Altman [34:54] – I hope you do, too. I’m sure you will. That’s a great place to leave it. People can read that document and call you up.

Vinod Khosla [34:59] – Yes.

Sam Altman [35:00] – Thank you very much.

Vinod Khosla [35:01] – Thanks. Thanks, Sam. This was fun.

Craig Cannon [35:03] – Alright, thanks for listening. As always, you can find the transcript and the video at blog.ycombinator.com. If you have a second, it would be awesome to give us a rating and review wherever you find your podcasts. See you next time.

Categories

Other Posts

ICYMI: Watch 40+ founders pitch at YC's Work at a Startup Expo

December 11, 2020 by Ryan Choi

Author

Y Combinator

Y Combinator created a new model for funding early stage startups. Twice a year we invest a small amount of money ($150k) in a large number of startups (recently 200). The startups move to Silicon